By Maryam Henein, Vaxxter Contributor and Founder, HoneyColony

Somewhere, on the other side of the planet, in a hidden corner of a tropical rainforest, a new virus is surely incubating. A pathological killer that could unleash a deadly plague at any time.

Ebola: Inside the Deadly Outbreak, produced for Discovery Channel (video since deleted from Youtube)

Ebola 101: Its Early Beginnings

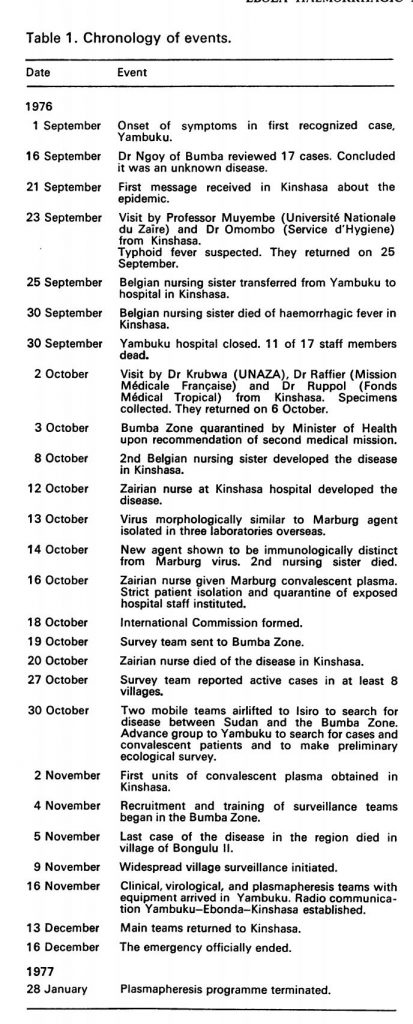

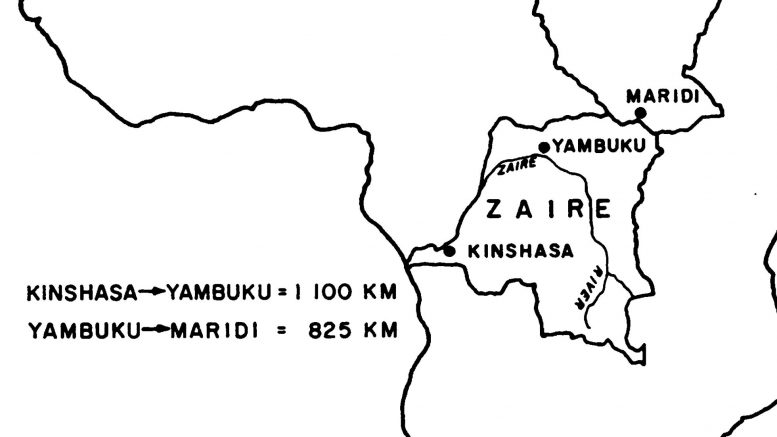

The Ebola virus gets its name from a little river in the region of the Bumba Zone of the Equateur Region. The Bumba Zone rests in Zaire’s northern frontier where the mysterious “illness” first appeared. Health officials didn’t know what it was at first; as is usually the case in the narratives presented to us.

It was 1976 when an outbreak occurred at the Yambuka Mission Hospital (YMH); a shanty hospital operated by Belgian Catholic missionaries since 1935. The mission had very little electricity, no diesel fuel, no functional laboratory, and no protective clothing for the staff writes a WHO 1978 bulletin.

The hospital served as the principal source of health care for, perhaps, 60,000 people in Yandongi and adjacent collectivities. People passing through Bumba Zone frequently traveled long distances to attend clinics there. The nun-nurses did not turn people away.

According to The Coming Plague by Laurie Garrett, who has been described as a “NWO Globalist,” the outbreak happened shortly after the sisters treated a man from the neighboring town of Yandongi. The man suffered from diarrhea, severe nosebleeds, and fever.

In Garett’s book, Patient Zero leaves two days later despite the sisters’ advice, and no one ever sees him again. And in another account by the WHO, he dies in the hospital.

Either way “he” conveniently turned out to be “a person completely unknown to the residents and authorities of Yandongi,” adds the WHO. Oftentimes the source of the virus remains mysterious or reaches folkloric proportions: e.g. it came from bat soup or a seafood market. There is no proof, and one at best can attempt to sort through the facts and put them together.

Infection Spreads

Within one week, several other persons who had received injections at YMH also suffered from Ebola hemorrhagic fever. Soon, the hospital was full of people who were heating up and basically bleeding uncontrollably from the inside out.

The WHO 1978 bulletin adds, “The index case in this outbreak had an onset of symptoms of five days following giving an injection of chloroquine for presumptive malaria at the outpatient clinic at (YMH).”

The horror was magnified by strange behavior. People snapped. Tore off their clothing. Ran out of the hospital, “screaming incoherently.”

Soon ‘virus hunters,’ scientists, and researchers from various Viral/Special Pathogen branches (e.g. the WHO, CDC), as well as The Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp, descended into Zaire, fearful yet fascinated. These groups suspected it was related to the Yellow Fever. They then settled that it was “a virus morphologically similar to Marburg virus, but immunologically distinct,” states the 1978 WHO Report.

They pulled samples from bedbugs, rats, bats, and other creatures that come into contact with humans. But there was no Ebola to study.

Meanwhile, Ebola virus antibodies were found in five persons who were not ill and had not had contact with the ” infected ” villages or the Yambuku hospital during the epidemic. “If these findings can be confirmed by an independent method of testing, they would suggest that the virus is, in fact, endemic to the region and should lead to further effort to uncover a viral reservoir in Zaire.”

But, to my knowledge, this was not — and has not — been proven.

Ebola: Troubling Facts And Preferential Treatments

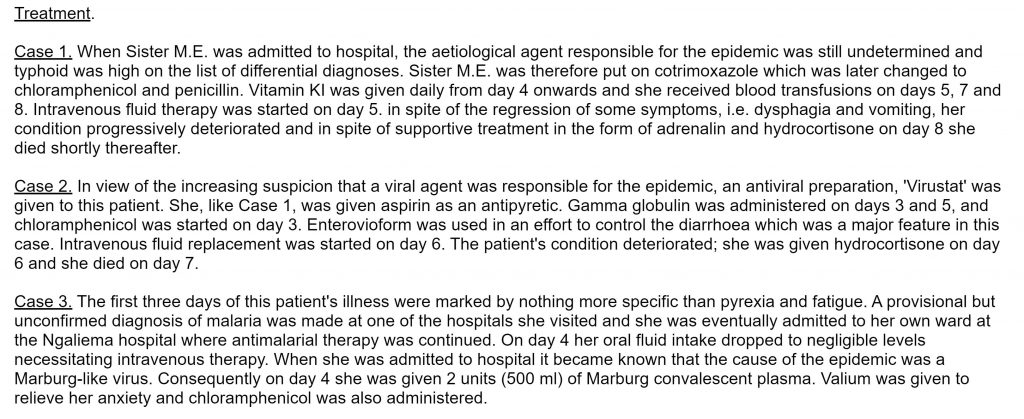

Between September 1st and October 24th, 1976, 318 cases of acute viral hemorrhagic fever occurred in northern Zaire. There were 280 deaths and only 38 serologically confirmed survivors.

According to lore, literally hundreds of people were involved in the hunt for the virus’s origin. In the end, the hunt cost more than $1 Million USD. But even with all this money and all these workers, the story of Ebola’s genesis is riddled with holes and inconsistencies.

Given all the personnel deaths, it didn’t take long for the Yambuku Mission Hospital to become nonfunctional. Interestingly, almost all subsequent cases of Ebola either received injections at the hospital or had been in close contact with another person who had Ebola. Most of these cases occurred during the first four weeks of the epidemic. Thereafter, the hospital was closed, with 11 of the 17 staff members dying from the disease.

Garett writes (in passing) that four of the sisters who initially died had been recently vaccinated. With What? Isn’t this worthy of more exploration? We don’t know for certain, although it’s likely it was for hemorrhagic fever. This also raises an eyebrow because, in many instances, the narrative is inverted like a dirty pair of underwear on an extended road trip. The unvaccinated are described as threats when in reality, it’s the vaccinated people who shed and are highly infectious.

The Wrong Vaccine?

The first Belgian nun, a midwife, became ill on September 14th and died on the 19th, 1976. It is possible that if the wrong vaccine was administered it could contribute to infectiousness or result in death. For instance, Nurse M.N received the Marburg plasma intravenously and died four days later, on October 20th.

In a third account I found this:

A hospital-based outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) occurred in Kinshasa, capital of Zaire, following the arrival of a sick nursing sister from the northern epidemic area. Her traveling companion, and a Kinshasa nurse who cared for her after her arrival in Kinshasa, also became ill and all three patients died after an illness lasting 7 to 8 days. The illness was characterized by fever, headache, myalgia, diarrhea, vomiting and later on a morbilliform rash, sore throat and hemorrhagic phenomena.

“It was a ‘little bit dicey to point to four Catholic missionaries,” writes The Coming Plague.

Zero Safety Measures

There is also a question of cross-contamination and sanitation. Or the lack thereof.

Reportedly:

Only Five syringes and needles were issued to the nursing staff each morning for use at the outpatient department, the prenatal clinic, and the inpatient wards. These syringes and needles were apparently not sterilized between their use on different patients but merely rinsed in a pan of warm water. Sometimes they were boiled at the end of the day. The surgical theatre had its own ample supply of instruments, syringes, and needles, which were kept separately and autoclaved after use.

Some of the mercenaries in the villages had recently returned after extensive traveling. Read: lots of contact with foreign bacteria or pathogens.

Finally, virological studies were limited. The only clinical laboratory test done on patients admitted to Yambuku Hospital was urinary protein. This was reported as uniformly positive and was used as a major diagnostic criterion by the nursing sisters early in the epidemic.

In fact “suspected cases were not closely examined, but medicines were still administered and arrangements were made for their isolation in the village. This stems from a report from the 1978 WHO Bulletin.

Zero Protocol And Preferential Measures

Even when there was no confirmation of the Ebola virus, patients were treated with antimalarial drugs, aspirin, antibiotics, and antipyretics to exclude other diseases common to the area.

At least three of the sisters were also given an assortment of arguably experimental treatments. Read more here.

Isn’t it odd then that when on November 5th, 1976, Geoffrey Platt, a lab tech at the former Microbiological Research Establishment in Porton Down in Wiltshire accidentally jabbed his thumb while taking a sample from an Ebola-infected guinea pig, his treatment bore no resemblance to the Zaire locals. He was treated with human interferon & convalescent serum. The course of his disease was mild & he fully recovered.

Incidentally, the Porton Down military installation was founded in 1916 and is the oldest chemical warfare facility in the world. It wasn’t until the 1960s that the government admitted the existence of the 7,000-acre site near Salisbury, United Kingdom.

Writing On The Wall: Whistleblower From the Mediterranean Sea

A few weeks after I started reading Garrett’s The Coming Plague, I came in contact with X, a journalist-turned-vaccine-whistleblower who didn’t want to use her name. She has been covering viral outbreaks for more than a decade. She has written about impending “Global Medical Martial” while shedding light on a litany of vaccine safety issues, including the World Health Organization’s (WHO)’s fraud, abuse, corruption, and mismanagement.

“We don’t have Ebola, it came out of a lab – I mean if you look at who developed these vaccines, they’re always are labs involved and the first Ebola outbreak […] the people who got Ebola in Zaire, Congo in 1976, were people who took a vaccine.”

Framed in this way… we observe a twist in the reported story.

“African In Origin”

According to X, officials eventually sent a military attaché, a commander colonel and the epidemiologist of the government” to the region. His name was Jean-Jacques Muyembe and he was appointed to investigate what they would soon call “Ebola.”

Piot (right), at the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp in 1976

Those who investigated Ebola included Jean-Jacques Muyembe, a tropical disease expert who studied in Belgium alongside Peter Piot, now well-known biological weapons and tropical disease expert. At the time of the first Ebola virus outbreak, he was only 27 years old.

Sukato Mandzomba, a member of the medical staff was the only employee who survived the infection and illness, writes Garret. Nature mentioned her in a 2017 piece titled Ebola survivors still immune to the virus after 40 years.

The official explanation is that Ebola came from somebody who was infected. Nurses in the hospital didn’t sterilize the needle and that caused the spread of the infection. On the surface, this sounds like a reasonable explanation. But, it doesn’t make sense in the context of the broad picture.

“Placed” Into Circulation

What if the virus was deliberately put into circulation, wonders X. “A thorough examination reveals the inklings of ulterior motives.”

In conclusion, the WHO itself stated that limited ecological investigations were done since the epidemiology of the outbreak “strongly suggested that the virus had been imported into the Bumba Zone.”

Back in 1978, the WHO conceded that much-desired information was never obtained. And that the means by which the virus was introduced cannot be confirmed.

As in the case of Marburg viruses, the source of Ebola virus is completely unknown beyond the simple fact that it is “African in origin.”

On October 27th an official account was given to disseminate to ‘press corps’. The findings were “conservatively designed to cast a sense of routine around a crisis,” writes Garett.

Even today consider that the timeline and origins of this virus remain fuzzy.

Part 2 Coming Soon: African Plague Reaches Beyond

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Like what you’re reading on Vaxxter.com?

Like what you’re reading on Vaxxter.com?

Share this article with your friends. Help us grow.

Join our list here or text MVI to 555888

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Maryam Henein is an investigative journalist, functional medicine consultant, and founder and editor-in-chief of HoneyColony . She is also the director of the award-winning documentary film Vanishing of the Bees, narrated by Ellen Page. She is currently being shadowbanned. Please follower her on Twitter

Be the first to comment on "Ebola 101: Early Beginnings – Part 1"